The Innovators Dilemma Summary

New technologies don’t just improve old markets—they create entirely new ones that the big players usually overlook… until it’s too late.

The Innovators Dilemma Summary

I know you’ve got a lot on your plate—juggling your 9–5, managing that side hustle, and still trying to keep life together. It’s a lot.

And you are showing up every day, doing your best. That’s why I want to share something that could make all the difference in your journey: real business wisdom that doesn’t waste your time.

You see, a lot of people fail in business not because they’re lazy or not smart—but because they didn’t see change coming.

They didn’t understand why good companies can fall apart and how tiny startups end up winning. That’s exactly what The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton Christensen breaks down.

This book is a wake-up call. It shows you why doing everything “right” can still lead to failure… unless you understand how disruption works.

In this quick Innovators Dilemma summary, I’ll give you the gold nuggets so you don’t have to read 250+ pages to get the message.

But if it hits you like it hit me, I’m begging you: get the full book. Keep it in your bag. Read it slowly, even if it’s just 5 pages a day.

The ideas here are that important—especially if you’re building something for the future.

Ready? Let’s dig in.

Why We Recommend this Book

It helps readers understand the hidden challenges of innovation and provides practical frameworks for spotting disruptive trends early and adapting effectively.

This book equips you with knowledge that can save time, money, and missed opportunities.

Plus, its lessons are timeless and relevant across many industries, making it a must-read for anyone serious about lasting success.

Questions to Ask Yourself before Reading The Innovators Dilemma

- Am I willing to question what I usually think about why big companies succeed or fail?

- Do I want to know why small new businesses sometimes beat big, famous companies?

- Am I curious about how new inventions can change or even destroy old businesses?

- Do I want to learn how to spot new ideas or products that could become very popular later?

- Am I open to learning how companies can organize themselves to try new and risky ideas?

- Do I want simple advice to help me make smarter choices when things in business are changing fast?

- Do I understand that what customers want can sometimes stop companies from trying new things?

The Innovator's Dilemma

Introduction

If you’ve ever wondered why big, successful companies like Kodak, Nokia, or Blockbuster collapsed—even though they had smart people, loyal customers, and deep pockets—The Innovator’s Dilemma explains it all.

Clayton Christensen introduces a powerful idea: that the very things that make companies great (like listening to customers, improving products, and focusing on profits) can also blind them to the next big thing.

Disruptive innovations often start out small, cheap, and easy to ignore… until they take over the market.

This book doesn’t just show you what happens—it shows you why it happens, and how to spot and ride the wave of disruption instead of being crushed by it.

Reading the summary will give you the key points. But the book itself is filled with real case studies, deep insights, and examples that make the ideas stick.

If you lead a team, run a business, or want to build one, this book will change how you see the future—and prepare you to survive and thrive in it.

Busy or not, you can’t afford to miss this.

Buy the book. Keep it on your shelf. Read it in sips or in one gulp. Either way, you’ll be glad you did.

Click on the Tabs Below to Read The Innovator's Dilemma Summary

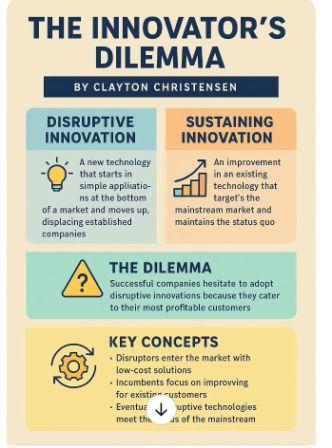

The Innovator’s Dilemma explains why successful companies often fail when faced with disruptive technologies—because the very strategies that make them industry leaders also prevent them from embracing innovations that start small but eventually transform entire markets.

Who Should Read The Innovators Dilemma?

Entrepreneurs and Startup Founders: To understand why disrupting established markets requires different strategies and how to spot opportunities that incumbents miss.

Corporate Leaders and Managers: To learn why successful companies can fail despite doing “everything right,” and how to foster innovation without killing disruptive ideas.

Product Managers and Innovators: To grasp how to manage new technologies and emerging markets, balancing core business demands with experimentation.

Investors and Business Strategists: To identify which companies are likely to succeed or fail based on their response to disruptive change.

Students of Business and Innovation: To build a strong foundation on the dynamics of innovation, market disruption, and organizational challenges.

Why Read it?

The Innovators Dilemma reveals critical insights into how and why established businesses struggle to adapt to disruptive technologies.

This knowledge is essential for anyone involved in innovation, strategy, or business growth in today’s fast-changing world.

It teaches readers to think differently about risk, customer focus, and organizational design to survive and thrive long-term.

Chapter 1: How Can Great Firms Fail?

Insights from the Hard Disk Drive Industry

Let’s say you run a very successful company. You have smart employees, happy customers, strong profits, and you’re always improving your product.

Everything is going well—and then suddenly, a small, scrappy startup shows up with a weaker, cheaper version of your product. You ignore it at first because it’s not good enough for your customers.

But a few years later, that startup has taken over the market—and your company is dying.

That’s the mystery this chapter explores:

Why do well-run companies—doing everything right—still lose to newcomers?

The Case Study: Hard Disk Drive Industry

Christensen uses the hard disk drive industry (basically the storage devices inside computers) to illustrate the problem.

In the 1970s and 1980s, computer makers used 14-inch hard drives in big mainframe computers.

Then came 8-inch drives. These were smaller and stored less data at first—but they were cheaper and more useful for minicomputers, a new type of computer.

The big companies making 14-inch drives ignored the 8-inch drives. They said, “Our main customers don’t want that low-storage stuff.”

But the minicomputer market grew fast, and companies making 8-inch drives improved them over time.

Eventually, 8-inch drives replaced 14-inch ones—and the big companies lost.

Then the same thing happened again with 5.25-inch drives for personal computers. And again with 3.5-inch drives for laptops.

Each time, the pattern repeated:

- A smaller drive with less capacity enters the market.

- Big companies ignore it because it doesn’t serve their current customers.

- New players adopt it, improve it, and grow fast.

- Big companies get wiped out.

Why Didn’t the Big Companies Fight Back?

Here’s the shocking part:

They didn’t fail because they were dumb or lazy. In fact, they were doing everything “right”:

- Listening to their best customers.

- Improving their current products.

- Investing in high-margin markets.

But those actions actually blinded them to the next big thing.

What Makes a Technology “Disruptive”?

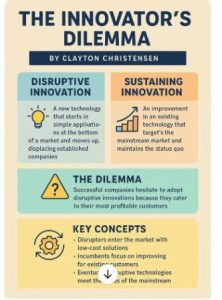

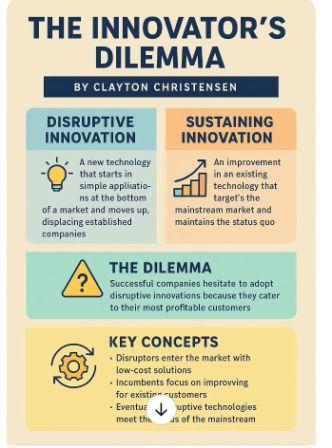

Christensen says there are two types of innovation:

- Sustaining innovations: These make a good product better—like adding more memory, speed, or features. Big companies love these.

- Disruptive innovations: These start out worse (lower performance, fewer features), but are cheaper, simpler, and serve a new or smaller market. Over time, they get better and challenge the status quo.

Disruptive innovations are easy to ignore at first. That’s the danger.

Example: Blockbuster vs. Netflix

This same story played out with Blockbuster and Netflix.

Blockbuster was the king of video rentals. Their customers wanted lots of stores, new movies, and convenience.

Then Netflix came along with DVDs by mail—no stores, no late fees, and a limited library.

Blockbuster laughed. “Our customers won’t go for that.”

But Netflix’s model improved, they moved into streaming, and—well, we all know how that ended.

Another Example: Nokia and Smartphones

Nokia was once the world leader in mobile phones.

They kept improving regular phones (better cameras, better designs).

But when the iPhone launched in 2007, Nokia dismissed it. “It’s too expensive and lacks buttons.”

But smartphones evolved, and Nokia never caught up.

So, What’s the Lesson?

Even the best companies can fail if they focus only on their current customers and existing technology. Disruptive innovations don’t look important at first—but if you ignore them, they can take your whole market.

Great firms fail not because they’re badly managed, but because they follow their customers too well.

To survive long-term, companies must be willing to:

- Look beyond current customer demands.

- Watch out for small innovations that seem weak.

- Invest in new markets, even if they seem tiny at first.

Why the Hard Disk Drive Industry Was Studied

Christensen chose this industry because it has a rich, well-documented history.

It experienced over 100 performance advancements and 8 major generations of drives in just 20 years.

It provided the perfect case study to understand how innovation impacts success and failure.

The Pattern of Failure

Christensen noticed a recurring pattern:

- New entrants introduced simpler, smaller, cheaper disk drives.

- Established companies stuck to improving their current products for existing (profitable) customers.

- Eventually, the new products improved enough to take over the mainstream market.

- The pioneers of the new technology won, and the old giants went bankrupt or became irrelevant.

3. Why Good Management Led to Failure

This part is especially counterintuitive:

The companies that failed were often the best managed—they listened to customers, hit growth targets, invested in R&D.

But by doing all those smart things, they missed the next wave.

Christensen’s insight:

It wasn’t bad decisions that led to failure—it was good decisions that made sense at the time.

Why Established Firms Didn’t Respond to Disruption

- They had strong customer relationships.

- Their business models couldn’t profitably pursue the low-margin, small emerging markets.

- Their processes, values, and structures weren’t designed for nimbleness.

- They were trapped by their success—making it risky to divert resources to uncertain innovations.

The Concept of “Technology Trajectories”

Christensen introduces technology trajectories by saying that:

- Each new technology starts at the low end but improves over time.

- The improvement curve often outpaces what customers actually need, meaning disruptors eventually offer “good enough” performance at lower cost.

Success plants the seeds of failure—because what makes companies great (serving current customers, improving performance, focusing on ROI) can make them blind to disruptive innovations.

To survive, companies must:

- Accept that small, strange-looking technologies could reshape the future.

- Be willing to explore new markets that don’t yet seem profitable.

- Sometimes break their own rules before someone else does.

Chapter 2: Value Networks and the Impetus to Innovate

Why do good companies seem locked in to doing only certain kinds of innovation, even when it’s obvious that the market is changing?

It’s because of something called the “Value Network.”

What is a Value Network?

Imagine you’re a business and you’re surrounded by a web of:

- Your customers

- Your suppliers

- Your investors

- And even your competitors

This web is your value network. It shapes how you make decisions.

It defines:

- What kinds of products you build

- What kinds of problems you care about

- And what kind of profits you expect

Example:

Think about Apple vs. Dell.

Apple’s value network is about design, innovation, premium experience.

Dell’s value network is about efficiency, cost-saving, speed.

They make different decisions, even when faced with the same technology—because of the value network they operate in.

How Value Networks Shape Innovation

Here’s the key idea:

Companies innovate in ways that serve their current value networks.

So when a new technology appears that doesn’t help their existing customers or profit goals, they’re unlikely to invest in it—even if it has massive future potential.

Example:Hard Disk DrivesBusinesses:

When 5.25-inch drives came out, big drive companies didn’t want them.

Why?:

- Their customers (mainframe makers) didn’t need them.

- The drives had lower performance.

- The profits seemed small.

But smaller companies in different value networks (like PC makers) loved them—so those startups jumped on the opportunity and won the market.

How This Becomes a Trap

Companies become trapped in a loop:

- Customers ask for better performance (sustaining innovation).

- Companies respond by improving the existing product.

- A disruptive product emerges, but doesn’t appeal to current customers.

- Company ignores it.

- That disruptive product improves and eventually kills the company.

It’s not stupidity—it’s just how value networks work.

Example: Toyota vs. Detroit

In the 1970s, American carmakers focused on big cars. That’s what their customers and value networks demanded.

Toyota came in with small, fuel-efficient cars—which American firms laughed off at first. “Our customers don’t want those.”

But Toyota found a new market: young people, budget-conscious buyers, people affected by the oil crisis.

That new market grew fast, and Toyota eventually beat the giants in their own game.

So, What’s the Lesson?

You can’t understand why companies succeed or fail just by looking at their technology.

You have to understand the value network they’re operating in.

To survive and stay ahead, a company must:

- Be aware of its value network “blinders”

- Be willing to step outside that network to explore new markets

- Recognize that what seems “unimportant” today may dominate tomorrow

Technology supply may outpace market demand—but that doesn’t matter if you’re locked into serving only your current customers.

Disruption is not just about technology. It’s about business models, customers, and culture.

Companies that want to ride the wave of innovation must learn to:

- Play in new value networks

- Serve new types of customers

- And embrace low-end or unproven innovations—before it’s too late.

Chapter 3: Disruptive Technological Change in the Mechanical Excavator Industry

In this chapter, Christensen zooms out of the computer world and dives into something more “old school”—mechanical excavators (used in construction and mining).

His goal is to show that disruptive innovation isn’t just a tech thing—it’s a universal business pattern.

The Big Question:

Why did hydraulic excavators (a new technology) take over so fast—and why didn’t the dominant mechanical excavator companies adapt?

Two Types of Innovations (Again):

Sustaining innovations = Make current products better (more powerful, more efficient).

Disruptive innovations = Simpler, cheaper, lower-performing at first—but improve rapidly and change the game.

What Happened in the Excavator Industry?

1. The Old Way: Cable-actuated (mechanical) excavators

These were heavy machines with wire ropes and pulleys.

Big players: Bucyrus-Erie, Northwest Engineering, etc.

These companies were successful and dominant.

2. The New Way: Hydraulic excavators

Used oil and pistons instead of cables and pulleys. Smaller, lighter, initially weaker and less precise.

First useful only for small jobs, like digging trenches.

At first, the hydraulic tech couldn’t compete with the big mechanical ones for large construction jobs.

But over time…

Hydraulic machines got better and stronger.

They could do more types of jobs.

They became more efficient, easier to use, and cheaper to maintain.

Eventually, they replaced mechanical excavators completely.

Why Didn’t the Big Companies Adapt?

Just like in the hard disk industry:

- The big firms ignored hydraulics at first—their customers didn’t need them.

- Their business models were built for big machines, sold in high-profit, large-scale markets.

- By the time hydraulics got good enough, it was too late—the disruptors had taken over.

- New Entrants Took the Lead

Companies like Caterpillar, Komatsu, and others (some of whom weren’t even in the excavator game before) embraced hydraulic tech early. - They sold to new customers in smaller markets.

- They were comfortable with lower margins and simpler machines.

- They grew fast—because they rode the wave of disruption while others stuck to the old ways.

Key Insight:

The companies that lost weren’t bad—they were just too good at serving their current customers.

They focused on:

- Bigger contracts

- Larger machines

- Higher profits

- They couldn’t justify investing in a low-end product that didn’t serve their existing market.

Real-Life Parallel: Think Smartphones

Remember Nokia and BlackBerry?

Both dominated the market with keypads and business phones.

When the iPhone launched in 2007, it lacked a physical keyboard, had fewer enterprise features, and was mocked.

But it was easier to use, touch-driven, and had apps that appealed to a new kind of user.

Result: Apple disrupted the industry. Nokia and BlackBerry couldn’t catch up.

Same pattern as the excavator industry.

Quick Takeaways :

- Disruption can happen anywhere—not just in tech.

- Disruptive innovations often begin in low-end or new markets.

- Established firms lose because they listen too closely to existing customers.

To survive disruption, companies must be willing to:

- Play in smaller, emerging markets

- Embrace initially inferior technologies

- Think long-term, not just about immediate profits

Chapter 4: What Goes Up Can’t Go Down

Once a company gets used to making a lot of money from big, high-end products, it becomes very hard for it to “go down” and compete with cheap, low-end, disruptive products—even when those are the future.

Imagine you run a luxury restaurant that sells fancy meals at $100 each.

Then a new food trend hits: people want fast, simple street food at $5.

You know it’s catching on. But if you start selling $5 bread:

- Your current customers might laugh at you.

- Your staff might be confused.

- Your profit margins would drop.

- Your investors would question your decisions.

Even if you wanted to jump into the street food market, it would hurt your current business. So what do you do? Most companies say: “It’s not worth it.”

And that’s how disruption wins.

Example: Disk Drive Industry

Clayton Christensen goes back to the hard disk drive companies and shows this over and over again:

When 14-inch drives dominated, the big companies made lots of money from them.

Then 8-inch drives came—smaller, cheaper, worse at first.

The big firms ignored them: “Our mainframe customers don’t want this.”

The same happened with 5.25-inch and later 3.5-inch drives.

Each time, a new, smaller form factor came, and the dominant companies refused to compete at the low end.

Why? Because they had gone up—they were selling high-end products with big profit margins. Competing at the low end felt like going backward.

Christensen Shows this with Data:

He tracks how profit margins, employee incentives, and customer demands all pushed big companies to focus on sustaining innovations—not disruptive ones.

Managers weren’t stupid—they just responded to the data.

Why make a $5 profit on a new, uncertain product…

When you could make $50 profit by selling an upgrade to your loyal, high-end customers?

So even when smaller drives started to gain traction, the top companies couldn’t justify making them.

Important Observation:

“What goes up can’t go down” means:

The higher your costs, reputation, and expectations grow, the harder it is to compete in smaller, scrappier, emerging markets.

Examples Outside Tech:

1. Toyota vs. GM :

GM made big cars. More profit per car. Luxury segments.

Toyota entered the U.S. market with cheap compacts—barely profitable.

GM ignored it at first. “We can’t make money on those.”

Toyota improved over time—and eventually competed in luxury too (think Lexus).

2. Airlines:

Full-service airlines (like British Airways or Delta) have high operating costs and expectations.

Budget airlines (like Ryanair or Southwest) started with no frills, low prices—and won a big chunk of the market.

Even when the big airlines tried to create budget spin-offs, most failed. Their cultures and cost structures just didn’t fit.

QuickTakeaways:

- Companies that go upmarket find it hard to go back down.

- Disruption often starts with unattractive customers and low profits.

- Even when leaders see disruption coming, their own structure, profits, and prestige make it hard to act.

That’s why new entrants, with fewer expectations and simpler models, win the disruption game.

If you’re a successful company making lots of money in a high-end market, how do you justify chasing something smaller, less profitable, and uncertain?

Most don’t. That’s why disruption keeps winning.

Chapter 5: Give Responsibility for Disruptive Technologies to Organizations Whose Customers Need Them

Big Idea

If you try to develop a disruptive innovation inside your existing business—serving your current customers—it will likely fail.

Why? Because your current customers don’t want it, and your company isn’t set up to support it.

So instead, you need to create a separate team, division, or even spin-off—one that can focus on the new market, with different goals and a fresh start.

Imagine you run a big photography studio that makes money from printing high-end wedding albums.

Now someone in your company suggests:

“Let’s make a cheap photo app that lets people edit and post pictures on their phones.”

Your current customers (professional photographers and brides) would say:

“We don’t want that. We need high resolution, perfect colour, and big prints.”

Your staff would say:

“There’s no money in $5 apps.”

So, even if the app idea is good, your studio kills it—because:

- It doesn’t fit your customers

- It threatens your core business

- It seems too small to bother with

This is what happens inside big companies with disruptive innovations.

Key Lesson: Serve the Right Customer

Christensen says you must give disruptive technologies to teams or units who serve customers that actually want them—not to your existing departments.

Because disruptive products are not for your current customers.

They are for new, emerging, or low-end customers who value something different (like low cost or convenience over performance).

Example: IBM and the Personal Computer

IBM was dominating the mainframe computer market—huge machines for big businesses.

When personal computers (PCs) started emerging, IBM’s main customers didn’t want them.

So IBM created a completely separate team in Florida (away from the main HQ).

This team had freedom from IBM’s existing structure.

They partnered with outsiders (Microsoft and Intel).

They launched the IBM PC—fast and efficiently.

This move helped IBM compete in the PC market early, even though it later stumbled.

Why did this work (initially)?

- The new team wasn’t trapped by existing IBM rules, pricing, customer demands, or bureaucracy.

- They were focused on the new market with different success metrics.

Why Internal Teams Often Fail at Disruption:

- It is done inside a large company

- Managers listen to the biggest customers (who usually don’t want disruptive tech).

- The company’s processes, pricing models, and performance targets don’t match what the disruptive market needs.

- Resources are allocated to what seems most profitable—usually sustaining innovations, not disruptive ones.

Examples:

1. Kodak and Digital Cameras:

Kodak invented the first digital camera in 1975.

But their main customers were photo labs and film buyers.

So they didn’t invest heavily—because it threatened their film business.

Meanwhile, others (Canon, Sony, and even phones) ran with it.

2. Netflix vs. Blockbuster:

Netflix started with mail DVDs, then streaming.

Blockbuster could’ve done the same—but their customers were still coming to stores.

By the time they reacted, it was too late.

Christensen’s Advice to Companies is:

- Don’t try to force disruptive projects into your existing organization.

- Create small, agile teams (or spin-off companies) with freedom to:

- Target new customers

- Accept low margins early

- Experiment without fear of “failure”

- Let these teams grow independently until the market is proven.

Quick Takeaway:

Disruptive innovations need their own space to grow.

Don’t judge them by the standards of your existing business—or they’ll never survive.

Chapter 6: Match the Size of the Organization to the Size of the Market

Big Idea

Disruptive markets start small—so big companies often ignore or mishandle them.

Clayton Christensen argues that if you want a disruptive idea to succeed, you need to match it with a team or organization that sees it as a big opportunity, not a distraction.

Let’s say you own a huge restaurant chain that’s used to making $50,000 per day.

Now someone suggests you start a tiny food truck that might earn $500 per day.

You’d probably think:

“That’s nothing! It won’t move the needle. Why bother?”

But for a small startup, that same $500/day is exciting—it can be profitable, flexible, and worth scaling up.

That’s the problem big companies face:

They’re too big to care about small opportunities, even when those small things grow into huge industries later.

Disruptive Innovations Start Small—So They Need Small Teams

Christensen shows that new, disruptive markets are:

- Unpredictable

- Unproven

- Small (at first)

So if you assign a giant business unit with a huge revenue target to work on a disruptive product, it will often:

- Ignore it

- Undervalue it

- Starve it of resources

- Drop it because “it’s not worth our time”

But if you put the idea in the hands of a small, hungry team or business, they’ll:

- Be excited about small wins

- Stick with it longer

- Be more flexible and creative

Example: Disk Drives

Christensen goes back to the hard disk drive industry:

A company focused on large computers tried to explore a smaller drive for laptops.

But the team in charge had a revenue target of hundreds of millions.

When the small drive only generated a few million in sales, they abandoned it.

Another smaller company picked it up—and succeeded—because even small revenues were a huge deal for them.

Example: Google vs. Startups

Google tried building social networks like Google+, but it never truly took off.

The teams working on it had huge expectations and were used to billions in traffic and revenue.

By contrast, Instagram started with a tiny team that was excited just to get a few thousand users.

They nurtured and improved the product slowly—eventually becoming massive.

Key Principle:

- Relative Success Matters

- A small market is a failure for a large company…

But it’s a success for a startup.

So, if a new idea is going to start small (which most disruptive innovations do), you need to match it with an organization that can see that small start as meaningful.

Christensen’s Strategic Advice:

- Spin off disruptive projects into smaller teams or even separate businesses.

- Don’t put them under pressure to immediately deliver huge returns.

- Let them grow organically—at the pace the market allows.

- Celebrate small wins—they often lead to breakthroughs.

Big companies fail to adopt disruptive innovations because:

- They expect early success to be big

- Their cost structure makes small markets unprofitable

- Their systems are optimized for big customers and large revenue

So unless they build smaller structures, they’ll kill the idea too early.

Quick Takeaway:

- Don’t feed a baby with an adult’s appetite.

- Let small innovations grow inside small structures until they’re strong enough to scale.

Chapter 7: Discover New and Emerging Markets

Big Idea

Disruptive innovations don’t just improve existing markets—they often create entirely new ones.

But here’s the catch: these new markets are unpredictable, so traditional market research methods don’t work.

To succeed, companies must learn to explore, experiment, and discover where the new market is and what customers actually value.

When companies launch products, they usually want to ask questions like:

- What’s the market size?

- What features do customers want?

- How much will they pay?

That works well for sustaining innovations (products that improve what already exists).

But for disruptive innovations, the answers often don’t exist yet—because the market hasn’t been created.

Example: Hard Disk Drives

Christensen explains how small disk drives were first seen as low-performance and irrelevant.

Mainframe computer makers didn’t want them.

But a new market emerged: desktop computers, portable computers, and eventually laptops—devices that needed smaller drives.

The first companies to succeed with small drives were the ones who:

- Didn’t try to force them into old markets

- Instead, explored new uses

- Found new customers who valued things like portability over raw performance

Why Big Companies Struggle Here:

Big companies are used to planning and forecasting. But with disruptive innovations:

- There’s no clear data

- There are no customers asking for it

- Early adopters may seem niche or unimportant

- Revenue may seem too small to care about

So, they don’t explore, or they drop the idea early.

Christensen’s Key Insight:

You can’t analyze your way into a new market.

You have to discover it through action, learning, and iteration.

Example: Apple’s iPod

When Apple launched the iPod, the market for MP3 players was small and fragmented. Traditional companies didn’t think there was much money in it.

But Apple didn’t just sell a music device—they:

- Created iTunes

- Made it easy to buy, store, and play music

- Created a new market experience around digital music

They discovered and shaped the market through experimentation.

Another Example: Airbnb

Traditional hotels ignored Airbnb early on because:

- It looked like a niche: renting out your couch to strangers

- The market seemed unprofessional and too risky

But Airbnb discovered a new market:

- People looking for cheaper, homey, or local experiences

- Hosts looking to earn side income

That new market didn’t exist in the usual hotel playbook, but it grew into a billion-dollar industry.

So, What Should Companies Do?

Christensen says companies should:

- Expect uncertainty.

- Don’t demand perfect data for decisions in new markets.

- Learn through trial and error. Launch, observe, adapt.

- Be patient for growth, but aggressive for learning.

- Use small teams to test ideas in new spaces—don’t scale too fast.

- Accept failures as part of the discovery process.

The Core Lesson:

Disruptive innovations often succeed not because someone knew exactly what would happen,

but because they explored what was possible.

Quick Takeaway:

You don’t “find” a new market—you create and discover it by taking smart risks, listening to feedback, and adjusting as you go.

Chapter 8: How to Appraise Your Organization’s Capabilities and Disabilities

Big Idea

A company’s strengths can become weaknesses when it faces disruptive innovation—not because it lacks talent, but because of how it’s structured, how decisions are made, and what it’s built to do well.

Christensen says that to understand whether your company can succeed with a new disruptive idea, you need to assess three things:

- Resources

- Processes

- Values

1. Resources: What you have.

These are the people, technology, products, relationships, money, and intellectual property your company owns.

Resources are easy to measure and easy to change. You can hire new people, buy tech, or partner with others.

For example:

Google has engineers, patents, brand trust—those are resources.

A small startup might have 5 people, a basic prototype, and hustle—that’s a different resource mix.

So if a new project needs a specific skill or tool, you can often fix it by adding or changing resources.

2. Processes: How you work.

These are the patterns your team uses to get things done:

- How do you develop products?

- How do you budget?

- How do you make decisions?

Processes are harder to change.

Why? Because they’re baked into how people operate every day.

For example:

A big company may have a 6-month budgeting cycle.

A startup may decide everything in a single Zoom call.

If your process is slow, risk-averse, or designed for efficiency, it may not allow fast experimentation—which is exactly what disruptive innovation needs.

3. Values: What you prioritize.

This is the hardest part to change.

A company’s values define:

- What kinds of customers are important?

- What size of opportunity is “worth it”?

- What kind of projects get funded or killed?

For example:

A large telecom company may only fund ideas that can make $100M+.

A small team may chase a $1M idea with full energy.

So even if a big company could build a great disruptive product, its values may reject it because the market is “too small,” “too risky,” or “off-brand.”

Christensen’s Message:

If you give a disruptive innovation to the wrong team—one with the wrong resources, processes, or values—you’re setting it up to fail.

Example : IBM

Christensen explains how IBM struggled to compete with smaller companies making personal computers.

Why?

Their processes were geared toward selling to enterprise clients

Their values made them ignore small, emerging markets

Even though they had resources (money, talent), their structure couldn’t move fast or cheaply enough

Eventually, they had to spin off the PC division to give it a fighting chance.

Example: Kodak

Kodak actually invented the digital camera.

But their values said: “Film makes us money.”

Their processes were all about selling film and prints.

So the disruptive product they invented?

They shelved it—and other companies beat them to the market.

What Should Companies Do?

- Be honest about your resources, processes, and values.

- Don’t assume you can do everything just because you’re big.

- If your processes or values don’t fit the new idea:

- Spin it off

- Give it to a team with the right fit

- Use separate teams or organizations when necessary—especially for disruptive projects.

Quick Takeaway:

It’s not enough to ask: “Do we want to do this?”

You must also ask: “Are we even built to do this?”

A company’s strengths are situational.

What helps you dominate one market can make you blind or slow in another.

The companies that win at disruption are the ones that recognize when their usual way of doing things won’t work—and create a new structure that can.

Chapter 9: Performance Provided, Market Demand, and the Product Life Cycle

Big Idea

Over time, technology improves faster than most customers’ needs.

This performance overshoot opens the door for simpler, cheaper technologies to enter from below—and disrupt.

Most companies work hard to make their products better—faster, stronger, more features.

But here’s the twist:

Customers don’t always need or want all those improvements.

Eventually, products become “too good” for what many people actually need.

When that happens, a simpler, cheaper, or more convenient alternative can sneak in—and disrupt the big players.

The Performance Trajectory Graph (as explained in the book):

Christensen introduces a helpful mental image:

One curve shows how fast a company’s technology improves over time.

Another curve shows how much performance customers actually need.

At first, customers want more power, more speed, more features.

So companies innovate and move up the curve.

But eventually, they surpass what most people care about.

That’s when disruption happens.

Example: Smartphones vs. Digital Cameras

Camera makers kept adding more megapixels, better lenses, advanced features.

Meanwhile, smartphones started adding “good enough” cameras.

For most people, smartphone cameras were:

- Convenient

- Portable

- Easy to share from

Even though DSLR cameras were better in performance, smartphones were good enough for the average person—and easier to use.

That’s classic disruption.

Another Example: Google Docs vs. Microsoft Word

Microsoft Word is feature-rich and powerful.

But many people just need to:

- Write text

- Share documents

- Collaborate in real time

Enter Google Docs:

- Fewer features

- Easier sharing

- Cloud-based collaboration

It wasn’t better on technical performance, but it met a growing need in a simpler, more accessible way.

Why Companies Miss It:

Because they’re listening to their best, most profitable customers, who often:

- Want more features

- Will pay more

This leads companies to overbuild and over-invest, ignoring new segments that seem:

- Too small

- Unprofitable

- “Not our customer”

But those segments grow.

Product Life Cycle Meets Disruption

In early stages, companies fight for performance gains to satisfy early adopters.

As the product matures, customer needs plateau.

When the product enters maturity, a disruptive tech often enters from below with:

- Simpler performance

- Lower cost

- New or overlooked users

What Should Companies Do?

- Watch for overshooting: Are you giving more than your average customer needs?

- Look at low-end or fringe users: What solutions are they adopting?

- Experiment with simpler versions of your product or service.

- Don’t dismiss “inferior” innovations too quickly—they might be the next big thing.

Quick Takeaway:

The race to improve performance can make you blind to simpler, cheaper innovations that meet real-world needs—and those are the ones that change entire industries.

Chapter 11: The Dilemma of Innovation: A Summary

Big Idea

This chapter brings together all the lessons from the previous chapters and explains why great companies fail—not because they’re bad, but because they do everything right according to traditional business logic.

But that same logic makes them vulnerable to disruptive innovations.

Successful companies listen to their best customers, focus on big markets, and aim to improve profits.

But disruptive innovations:

- Start in small, unprofitable markets

- Offer lower performance (at first)

- Are often ignored or rejected by mainstream customers

So if companies follow the rules of good management, they will almost always reject disruptive innovation—until it’s too late.

What Makes Disruptive Innovations So Dangerous:

1. They serve different customer needs.

Disruptive products often appeal to new or low-end users that established companies aren’t serving well.

2. They start small.

In the beginning, these markets look unattractive to big firms—too small, not profitable, no immediate returns.

3. They improve over time.

Though they start off inferior, disruptive products get better fast—and soon meet the needs of mainstream users too.

Why Great Firms Miss the Threat:

Christensen outlines several reasons:

1. Customer-Driven Thinking Backfires

Companies prioritize what existing customers want.

But customers usually don’t ask for disruptive innovations because:

- They’re not aware of them

- They don’t see the need—yet

2. The Market Seems Too Small

Disruptive innovations often emerge in niche markets.

Big companies don’t want to invest in small segments that won’t move the needle.

3. Financial Pressure

Managers are taught to:

- Maximize ROI

- Cut costs

- Invest where profits are highest

That logic causes them to:

- Avoid small, risky markets

- Delay action until the new innovation becomes “obviously” important—often too late

The Solution:

Managing Disruption Differently

Christensen doesn’t just highlight the problem—he offers practical strategies for dealing with it.

Here are his main suggestions:

1. Create Separate Teams or Units

Set up small, independent teams focused on disruptive innovations.

These teams should:

- Be free from the parent company’s culture

- Focus on small markets

- Grow organically with the innovation

Example: IBM created a separate unit to build its PC in the 1980s—which saved the company during the personal computer revolution.

2. Focus on Learning, Not Just Planning

Because disruptive markets are uncertain, success comes from experimentation, not big plans.

You must test, learn, and iterate.

3. Be Willing to Fail Small

Invest in small bets that might not pay off right away.

The goal is to learn and adapt—not to maximize profit from day one.

4. Change How You Evaluate Opportunities

Instead of just asking:

- Is this a big enough market?

- Will this be profitable this quarter?

Ask:

- Is this solving a job that’s being underserved or ignored?

- Could this market grow?

- Is this the kind of innovation that could disrupt us later?

Analogy: Kodak

Kodak actually invented the digital camera in the 1970s.

But their management rejected it because:

- It wasn’t as good as film

- It would eat into their very profitable film business

- Their customers weren’t asking for it—yet

They did the “right” thing for the business—but they missed the disruptive future.

Eventually, digital photography destroyed Kodak’s dominance.

Disruption is not a technology problem.

It’s a management problem.

Even the best-run companies fail if they apply the wrong logic to the wrong type of innovation.

Christensen urges leaders to recognize disruption early, set up autonomous units, and use different metrics to nurture these innovations while they’re still small and uncertain.

Quick Takeaway:

The very things that make companies great—their focus on profits, core customers, and efficiency—can also make them vulnerable to disruptive change.

To survive disruption, you must think differently, act early, and be willing to invest in small, uncertain, and initially unprofitable innovations.

Here are the things you need to start doing right now to implement the strategies in this book:

1. Regularly Scan for Disruptive Innovations in Your Industry

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Step 1: Set a weekly 30-minute calendar reminder to research emerging technologies and startups in your industry.

Step 2: Use Google Alerts or tools like Feedly to track keywords like “disruptive technology in your industry.

Step 3: Subscribe to 2–3 innovation-focused newsletters (e.g., TechCrunch, CB Insights).

Step 4: At the end of each month, create a 1-page summary of key innovations and rank them by their potential threat or opportunity.

Timeframe:

Initial setup: 1–2 hours

Ongoing: 30–60 minutes per week

Challenges & Solutions:

Challenge: Feeling overwhelmed by too much information

Solution: Set a limit (e.g., focus on just 3 key articles or trends per week).

Metrics to Track Progress:

- Report on emerging innovations logged monthly

of potentially disruptive threats identified in 3 months - Action taken on any single innovation (e.g., follow-up research, customer interviews)

2. Talk to Non-Customers & Fringe Users

Disruptive innovations often appeal to people your business isn’t serving well.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Step 1: Identify 3–5 groups of non-customers or underserved customers.

Step 2: Reach out via surveys, informal interviews, or Reddit forums to ask:

- What solutions do they use?

- What frustrates them about current options?

- What features are “too much” or “not enough”?

Step 3: Document patterns and unmet needs in a shared spreadsheet or Notion board.

Timeframe:

Initial outreach: 1 week

Insights collection: 2–3 weeks

Challenges & Solutions:

Challenge: Low response rates

Solution: Offer small incentives (e.g., gift cards, early access) or start with personal connections.

Metrics to Track Progress:

Number of non-customers interviewed

about un-met needs or recurring patterns identified

from insights implemented into product ideas or improvements

3. Set Up a Small Innovation Unit or Team

Disruptive ideas need space to grow—away from the pressure of core business metrics.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Step 1: Identify 1–2 people (or yourself) to explore disruptive ideas part-time.

Step 2: Define clear boundaries: budget, time, customer segment (often not your current customers).

Step 3: Choose one idea or market segment and commit to testing it over 90 days.

Step 4: Track experiments and learning, not just revenue.

Timeframe:

Set-up: 1–2 weeks

Pilot or trial period: 90 days

Challenges & Solutions:

Challenge: Lack of resources or executive support

Solution: Start small—use low-cost tools and frame it as a “learning lab” rather than a business risk.

Metrics to Track Progress:

- Check the progress of the ideas tested in 90 days

- Learning gained per test (documented insights)

- Team hours spent on disruptive experiments vs. core business

4. Create a Disruption Dashboard

Track performance improvements vs. market demand to spot over-served segments and openings for disruption.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Step 1: List all current product features and rank them by how much value they provide to different user segments.

Step 2: Identify any areas where your product over-delivers (costs you more than customers care about).

Step 3: Compare this to simple, cheaper competitors—are they winning on price or simplicity?

Step 4: Build a dashboard (in Excel or Notion) to track:

- Feature usage rates

- Customer satisfaction

- Competitor pricing trends

Timeframe:

Setup: 2 weeks

Review: Monthly

Challenges & Solutions:

Challenge: Accessing good data

Solution: Use surveys, product analytics, and sales team feedback as proxies.

Metrics to Track Progress:

- The number of underused features identified

- Cost savings or simplification opportunities spotted

- Adjustments made based on dashboard insights

5. Pilot a Disruptive Product Idea for an Emerging Market

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Step 1: Choose a niche or low-end market your current business ignores.

Step 2: Develop a simple MVP (Minimum Viable Product) that prioritizes affordability, simplicity, or accessibility.

Step 3: Launch quietly with a test audience (e.g., freelancers, students, developing markets).

Step 4: Measure learning and adjust rapidly—focus on fit, not perfection.

Timeframe:

Research & MVP: 4–6 weeks

Pilot or trial period: 60–90 days

Challenges & Solutions:

Challenge: Internal resistance or fear of cannibalization

Solution: Emphasize that this serves different customers and won’t affect current core business—yet.

Metrics to Track Progress:

- Track progress of users acquired in pilot

Retention and feedback scores - Learning milestones met (e.g., “We validated the need for X…”)

Start Small, Learn Fast

The Innovator’s Dilemma teaches that the goal is not immediate success, but early discovery and adaptability. Disruption starts slowly—your job is to be ready before it becomes urgent.

Clayton M. Christensen (1952–2020) was a renowned American academic, business consultant, and author.

He was a Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and is best known for developing the theory of disruptive innovation, a concept that has transformed how businesses think about growth and competition.

Christensen earned degrees from Harvard University, Oxford University (as a Rhodes Scholar), and Brigham Young University.

He authored or co-authored over a dozen influential books, including The Innovator’s Solution, How Will You Measure Your Life?, and Competing Against Luck.

He was widely respected not just for his brilliant mind but also for his humility and commitment to helping others apply innovation principles to solve real-world problems—including education, healthcare, and personal growth.

Book Details

Title: The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail

Author: Clayton M. Christensen

Publisher: Harvard Business Review Press

Publication Date: First published in 1997

Genre: Business, Innovation, Management, Strategy

Format: Available in Hardcover, Paperback, eBook, and Audiobook

ISBN-13: 978-1422196021

Page Count: Approximately 288 pages

Language: English

Audience: Entrepreneurs, business leaders, managers, product developers, and innovators

The Innovators Dilemma Quiz

-

Start The Innovators Dilemma Quiz