Summary of The Lean Startup by Eric Ries

We need to seek to understand what customers truly desire, not just what they say they want or what we assume they should want.

The Lean Startup Summary

Starting and running a business is hard. The Lean Startup makes it easier.

If you have been wondering when you will have the time to read The Lean Startup, we have put together the Lean Startup Summary to help you get the key ideas from the book in minutes.

We have only scratched the surface with this summary. Want more juicy details from the book?

Get the book if you don’t have it already. You can also listen to the audiobook . Lets get started.

Why We Recommend this Book

The Lean Startup is essentially for anyone currently facing the uncertainty of a new project because it prevents the common trap of wasting months building something that nobody actually wants.

By following these steps, you will stop relying on gut feelings and start seeing your business as a series of experiments that reveal exactly what your customers value. Its scientific approach has become the standard for modern founders and innovative leaders who prioritize real progress over the comfort of a traditional business plan.

The Lean Startup

Questions to ask yourself before reading The Lean Startup

- How much time am I willing to waste? Am I okay with spending six months building a perfect product only to find out nobody wants it, or would I rather look a bit unpolished now to find the truth faster?

- Do I care more about being right or being successful? Am I prepared to see my favourite idea proven wrong by data, and am I brave enough to change my entire strategy if the customers tell me I am on the wrong path?

- Am I hiding behind my computer? Am I making lists, designing logos, and researching because it feels safe, or am I actually willing to go out and talk to real strangers about their problems today?

- What is my actual goal? Is my goal to cross items off a to-do list so I feel productive, or is it to create validated learning that actually moves my project forward?

- Do I have a plan B for my ego? When I hit a wall, is my first instinct to work harder on the same bad idea, or can I stop, ask why five times, and adapt my behaviour?

If these questions make you feel a little uncomfortable, you will get the most out of this book.

Overview: The Lean Startup by Eric Ries

What if you spend months (or even years) building a product, only to find out nobody wants it?

Most startups fail not because their founders aren’t smart or hardworking, but because they waste time, money, and energy on ideas based on assumptions rather than real customer needs. That’s where The Lean Startup by Eric Ries changes everything.

This book introduces a new way to build businesses, faster, smarter, and with less waste.

Instead of following a rigid plan, it teaches you to test ideas early, gather customer feedback, and adapt quickly using the Build-Measure-Learn loop. By starting with a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), you avoid costly mistakes and focus only on what truly works.

This book has had a profound influence on how startups and large companies approach product development and innovation and has led to a lot of business success

Let’s dive in.

Click on the Tabs Below to Read The Lean Startup Summary

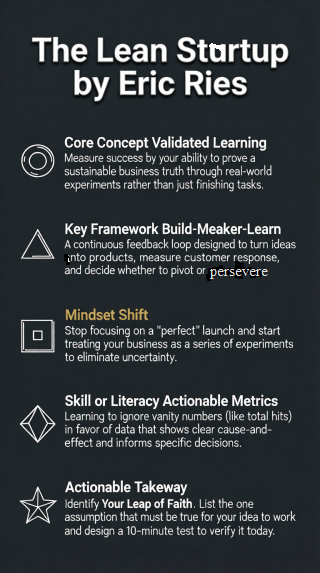

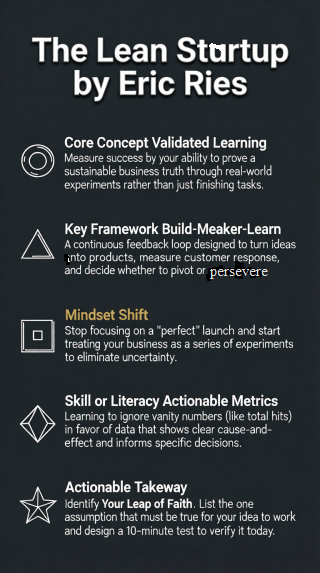

Success in entrepreneurship is achieved by treating every business idea as a scientific experiment, using the Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop to eliminate waste and discover a sustainable path through validated learning.

Who This Book The Lean Startup for and Why?

If you are trying to decide if this book is worth your time, think about where you are in your current project. It is a great fit if you fall into one of these groups:

- The Over-Planner: You have a notebook full of ideas but you are stuck in the research phase because you want everything to be perfect before you launch. This book will help you stop overthinking and show you how to start with a small experiment that proves if your idea is actually worth the effort.

- The Burnt-Out Builder: You have already spent months and a lot of money building a product, but when you finally showed it to the world, nobody cared. You will gain a specific system to stop the bleeding and find out exactly where you went wrong so you do not repeat the same mistake with your next version.

- The Corporate Innovator: You work in a large company and feel like every new idea gets killed by meetings and red tape. This book gives you the tools to create a safe space for innovation so you can move as fast as a startup without putting the whole company at risk.

Who it is not for right now

This book is not ideal for you if you are currently in a maintenance phase where your business is already stable and growing predictably. If your biggest problem is just managing a large staff or optimizing a proven system, you might find the constant experimentation and pivoting a bit distracting. This is a book for the chaos of the beginning, not the comfort of the middle.

Introduction

A New Way to Think About Success

To understand the arguments in The Lean Startup, you first have to unlearn a lot of what we were taught about good management. Eric Ries starts with a bit of a wake-up call: most startups fail. But here is the truth: they don’t fail because they have bad ideas or because people don’t work hard enough. They fail because they are following a manual that was written for a completely different kind of world.

The Myth of the Great Plan

Traditional management is built on the idea that if you study a problem long enough, you can predict the future.

In a big company that has been around for fifty years, this works. They know their customers, they know the market, and they can forecast next year’s sales with decent accuracy.

But if you are starting something new, you are operating in a fog of uncertainty. You don’t actually know who your customer is or if they want what you are building. When you try to use old-school management, like creating a 20-page business plan before you’ve even sold a single item, you are essentially driving a car toward a cliff while looking at a map of a different city.

What Is a Startup, Really?

Ries defines a startup in a way that might surprise you. He says it is any human institution designed to create something new under conditions of extreme uncertainty.

This means a startup isn’t just two guys in a garage. If you are a solo freelancer trying a brand-new service, or if you are a manager at a giant bank trying to launch a new type of account, you are a startup founder.

The context doesn’t matter as much as the uncertainty. If you don’t know for sure what is going to happen next, you can’t manage by a rigid plan. You have to manage by learning.

The Engine of Validated Learning

This is the most practical part of the introduction. Ries argues that the goal of a startup isn’t just to make stuff or spend money. The true goal is validated learning.

Think about it like this. Imagine you want to start a gourmet dog food delivery service.

- The traditional way: You spend six months renting a kitchen, designing fancy packaging, and hiring a delivery driver. You launch, and nobody buys it. You just wasted six months and thousands of dollars.

- The Lean Startup way: You spend one afternoon making a simple flyer. You walk through the local park and see if people will actually give you their email address to sign up for a trial.

In the second scenario, you learned something real. You didn’t just guess. You validated whether there was interest before you spent the big bucks. This is the idea you should use every day: ask yourself, what is the cheapest, fastest way I can prove my idea is actually right?

A Challenge to Your Assumptions

Let’s pause here. Most people hear this and think, okay, so I should just launch a crappy product and see what happens?

Stop right there. This is the biggest mistake people make. Being lean does not mean being cheap or being sloppy. It means being scientific. If you release a broken product and people hate it, you haven’t learned if they hate the idea or if they just hate that it is broken. You have to be very intentional. You aren’t just throwing things at the wall. You are running a specific experiment to answer a specific question.

Why This Is Hard to Do

I will be honest with you: this is emotionally difficult. We like plans because plans feel safe. It feels productive to sit in your office and color-code a spreadsheet. It feels scary to go outside and have a stranger tell you your idea is useless.

The introduction makes it clear that entrepreneurship is management. It is just a different kind of management. Instead of measuring progress by how many features you finished, you measure it by how much you have learned about what customers actually value.

How to Start Using This Today

If you want to apply this right now, look at your biggest project.

- Identify your biggest assumption. What is the one thing that must be true for this to work?

- Find the smallest possible way to test that assumption.

- Don’t wait until it’s perfect. Perfect is the enemy of learning.

This approach is incredibly practical because it saves you from the heartbreak of building something nobody wants. It is a bit of a gut punch to realize your great plan might be wrong, but it is much better to realize it on day three than on day three hundred.

Chapter 1: Start

Chapter 1 is where Eric Ries lays out the philosophy that changes how you view your daily work. He stops talking about the big picture and starts talking about the nitty-gritty of how startups actually function.

Entrepreneurship is a Kind of Management

This is the most important sentence in the chapter. Most people think management is for boring corporate offices and entrepreneurship is for wild, creative geniuses. Ries says that is a lie. Because a startup is so uncertain, it needs more management, not less.

Think about it this way. If you are a pilot flying a commercial jet on a clear day, you can put it on autopilot. That is traditional management.

But if you are a pilot flying a small plane through a hurricane, you have to be at the controls every second, making constant adjustments. That is startup management.

The Goal Is Not to Build a Product

This is a hard pill to swallow. You might think your goal is to build a great app or open a successful store. Ries argues that in the beginning, your goal is actually to build a sustainable business.

The product is just the tool you use to see if the business works. If you spend all your time making the product perfect but no one wants to buy it, you have failed at your real job.

You have to shift your focus from building stuff to learning what people want.

The Five Principles of the Lean Startup

Ries introduces five principles that serve as the backbone for everything else in the book:

- Entrepreneurs are everywhere: You don’t have to be in a garage. You can be in a massive corporation or a tiny non-profit. If you are creating something new under uncertainty, you are an entrepreneur.

- Entrepreneurship is management: It requires a specific set of tools designed for uncertainty.

- Validated learning: Progress is measured by how much you have learned about the customer, not by how many lines of code you wrote.

- Build-Measure-Learn: This is the feedback loop. You build a small experiment, you measure the results, and you learn if you should keep going or change direction.

- Innovation accounting: You need a way to measure success that isn’t just about money. You need to track the numbers that actually prove your business is growing.

A Challenge to Your Definition of Success

Let’s stop for a moment. Most people measure a successful day by how much they got done. Did you clear your inbox? Did you finish the website?

Here is the mistake: You can be 100 percent efficient at doing something that doesn’t matter. You can work 14 hours a day and still be wasting your time.

In a startup, the only work that matters is the work that leads to validated learning. If you are working hard on a feature that no one will ever use, you are essentially doing nothing.

Why This is Practical

This chapter is especially useful because it gives you permission to stop trying to be perfect. If your goal is learning, then failing early is a win.

If you spend $50 to run an ad for a product that doesn’t exist yet, and no one clicks on it, you just saved yourself $50,000 in development costs. You didn’t fail; you just learned something very valuable very cheaply.

This is a massive weight off your shoulders if you can learn to embrace it.

How to Use This in Real Life

To apply Chapter 1, you have to stop thinking of yourself as a creator and start thinking of yourself as a scientist.

- Every new idea is a hypothesis.

- Every product launch is an experiment.

- Every customer interaction is data.

The moment you start treating your work this way, you stop being afraid of being wrong. You realize that being wrong is just a step on the way to being right.

Chapter 2: Define

Chapter 1 was about the mental shift of starting, Chapter 2 is about setting the boundaries of what you are actually doing. Eric Ries knows that the word startup is thrown around a lot, so he uses this chapter to give it a very specific, practical definition that you can use to figure out if these rules apply to you.

The True Definition of a Startup

Ries defines a startup as a human institution designed to create a new product or service under conditions of extreme uncertainty.

This is a huge deal because it removes the typical imagery of a tech founder in a hoodie. Notice what he doesn’t mention:

- He doesn’t mention the size of the company.

- He doesn’t mention the industry.

- He doesn’t even mention that it has to be a for-profit business.

If you are a teacher trying a brand-new way to grade papers in a school where no one knows if it will work, you are a startup founder.

If you are a middle manager at a legacy insurance company trying to launch a new internal portal, you are a startup founder. The unifying factor is the extreme uncertainty. If you don’t know who the customer is or what the product should be, you are in a startup.

The Role of the Intrapreneur

Ries spends time talking to those of you working inside big companies. He calls these people intrapreneurs.

Often, these people are more frustrated than solo founders because they have to fight the old-school management systems of their own companies while trying to innovate.

Chapter 2 argues that big companies need to treat these internal projects as startups. They shouldn’t be managed with the same rigid yearly budgets and ROI forecasts as the established departments.

They need room to experiment and room to fail, or the innovation will die before it ever gets a chance to breathe.

A Challenge to Your Identity

Here is a place where many people get stuck. We love titles. We love being a Director of Marketing or a Senior Developer.

Pause and look at this: In a startup environment, your traditional title is almost meaningless. If your title is Lead Designer, but no one wants the product you are designing, you are not actually providing value. Your real job in the early stages of a startup is to be an entrepreneur first and a designer second.

This means you have to be willing to do whatever is necessary to find a sustainable business model, even if it is outside your job description.

The Engine of Growth

Ries introduces the idea that every startup has an engine of growth.

This is the mechanism that allows the startup to become sustainable over time. Whether it is viral growth, paid growth, or sticky growth, you need to identify which engine you are using.

The goal of your definition phase is to figure out which engine makes sense for your specific uncertainty. You aren’t just building a product; you are tuning an engine.

How to Use This Today

To apply Chapter 2, you need to look at your current project and ask yourself a few hard questions:

- Is this truly a startup, or is it just a project with a clear path? (If the path is clear, you don’t need Lean Startup; you just need good traditional management).

- Who is the entrepreneur in charge? There needs to be one person who feels the weight of the uncertainty.

- Are you measuring success by how well you followed the plan, or by how much uncertainty you have removed?

By clearly defining what you are doing, you stop wasting energy trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

You accept that you are in a state of uncertainty and you start using the tools designed to handle it.

Chapter 3: Learn

In Chapter 3 Eric gets into the heart of the Lean Startup philosophy. Eric Ries calls this chapter Learn because he wants to redefine what progress looks like.

In a normal job, progress is finishing your to-do list. In a startup, progress is learning how to solve the customer’s problem.

The Trap of Vanity Metrics

Ries starts by warning us about a very human mistake: falling in love with numbers that make us feel good but don’t actually matter. He calls these vanity metrics.

Imagine you launch a new blog. You see that 5,000 people visited your site today. You feel like a rockstar. But then you look closer and realize that 4,999 of those people left after three seconds and never came back.

That 5,000 number is a vanity metric. It looks great on a chart, but it doesn’t prove you have a business.

True learning comes from actionable metrics. These are numbers that tell you exactly what you need to do next. For example, if you see that only 1 percent of people are clicking your sign-up button, you know exactly what you need to fix.

What Is Validated Learning?

This is the most important concept in the chapter. Ries argues that startups often suffer from a lot of waste. Not just wasted money, but wasted time and effort. People work incredibly hard to build features that no one ends up using.

Validated learning is the process of demonstrating, with real data from real customers, that you have discovered a sustainable business truth.

- It is not just a good idea.

- It is not just a survey where people say they will buy your product.

- It is actual behaviour.

If you can prove that customers are willing to pay for your service, you have achieved validated learning. Everything else is just a guess.

A Challenge to Your Hard Work

Here is where I want to challenge your assumptions. We have been taught since we were kids that hard work is its own reward.

But here is the truth: In a startup, if you work 80 hours a week to build something that doesn’t solve a customer problem, you haven’t just failed, you have efficiently wasted your life.

It is a painful realization. It means that all those late nights and all that stress were for nothing.

The Lean Startup method is designed to save you from this. It forces you to stop and ask: Am I actually learning anything?

The Scientist Mindset

To use the principles in Chapter 3, you have to start thinking like a scientist. A scientist doesn’t get depressed if their experiment fails.

They just look at the data and say, “Interesting. My hypothesis was wrong. Now I know what to try next.”

You should do the same with your business.

- Your idea is a hypothesis.

- Your product is the experiment.

- The customer’s reaction is the data.

If you approach your work this way, you stop being afraid of failure. Failure is just free data that helps you get closer to the truth.

How to Apply This Today

Look at your current project and find one thing you are 100 percent sure of. Now, ask yourself: How do I know this is true?

If your only evidence is that it sounds like a good idea or that your friends like it, you haven’t validated anything.

- Go out and find a way to test that assumption today.

- Don’t build a whole product. Just find a way to see if people will take the first step you want them to take.

This shift from building to learning is the secret to moving fast without going in circles.

Chapter 4: Experiment

This chapter focuses on the practice. Eric Ries argues that you should stop looking at your startup as a business and start looking at it as a scientific experiment.

Stop the Just Do It Mentality

There is a common belief in the startup world that you should just put your head down and build until you launch. Ries calls this the just do it school of thought. He thinks it is dangerous.

If you just do it without a clear hypothesis, you will likely end up with a pile of features that nobody wants. Instead of a grand launch, Chapter 4 advocates for a series of small experiments. Each experiment is designed to test a specific part of your business plan.

The Two Leap-of-Faith Hypotheses

Every business plan relies on certain assumptions that must be true for the business to succeed. Ries calls these leap-of-faith assumptions. In this chapter, he focuses on the two most important ones:

- The Value Hypothesis: Does the product actually deliver value to the people using it? Don’t ask them if they would use it. Run an experiment to see if they do use it.

- The Growth Hypothesis: How will new customers find out about the product? Will they find it through word of mouth, or will you have to pay for every single user?

The Zappos Story: A Perfect Experiment

One of the best examples in the book is how Zappos started. Nick Swinmurn had the idea that people would buy shoes online.

- Traditional way: Raise millions of dollars, build a massive warehouse, and buy thousands of pairs of shoes.

- The Zappos way: Nick went to a local shoe store, took photos of their shoes, and put them on a simple website. When someone bought a pair, he went back to the store, bought the shoes at full price, and mailed them himself.

He was losing money on every sale, but he was gaining validated learning. He proved the value hypothesis (people will buy shoes online) without spending a fortune on infrastructure.

A Challenge to Your Need for Perfection

Let’s talk about a mistake almost everyone makes: waiting for the product to be perfect before showing it to anyone.

Think about this: If your experiment is truly an experiment, it doesn’t need to be perfect. In fact, if it is perfect, you probably waited too long.

An experiment is not just a theoretical inquiry; it is your first product. If you are afraid to show it to people because it looks a bit messy, you are prioritizing your ego over your learning.

Why This Is Especially Practical

This chapter is a lifesaver for anyone with limited resources. It tells you that you don’t need a big team or a big budget to start. You just need a clear question and a way to test it.

If you can find ten people who are willing to use your messy prototype, that is a much better sign of success than having 10,000 people follow your social media page. It shifts your focus from looking successful to being successful.

How to Apply This Today

Break your big vision down into small, testable pieces.

- Identify your biggest leap-of-faith assumption. What is the one thing that, if it is wrong, the whole business falls apart?

- Design an experiment to test that assumption this week.

- Find early adopters, the people who have the problem so badly they are willing to use a half-finished solution.

Don’t worry about scaling yet. Right now, your only job is to see if your hypothesis holds up in the real world.

Chapter 5: Leap

Chapter 5 is titled Leap because every entrepreneur eventually has to make a leap of faith.

Eric Ries argues that while you can use data to guide you, every business starts with a few massive assumptions that have no proof yet.

Strategy Is Built on Assumptions

Ries explains that a business strategy is essentially a set of guesses about how the world works. He calls the most important ones leap-of-faith assumptions. If these are wrong, the whole business fails.

Instead of writing a 50-page business plan, your job in this phase is to identify these assumptions and test them as quickly as possible. The two most critical ones are:

- The Value Hypothesis: Do customers actually find this valuable once they use it?

- The Growth Hypothesis: Once people find it valuable, how will it spread?

The Danger of the Genchi Gembutsu

Ries borrows a term from Toyota: Genchi Gembutsu, which means go and see for yourself. The big mistake entrepreneurs make is sitting in their office looking at spreadsheets and market reports.

You cannot understand your customer from a distance. You have to get out of the building and talk to them.

You need to see the look on their faces when they use your product. This first-hand customer archetype is much more valuable than any demographic data you can buy.

Don’t Analyze Until You Paralyze

Stop right there. A lot of people hear the word scientific and think they need to spend months researching.

This is a trap. You can spend forever analyzing a market, but you won’t truly know anything until you put a product in a customer’s hands.

The goal of Chapter 5 is to move from analysis to testing as fast as humanly possible.

The Role of the MVP

This chapter introduces the idea of the Minimum Viable Product (MVP). The MVP is the version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort.

Think of it like this:

- If you want to build a self-driving car, don’t start by building a wheel.

- Start by finding a way to test if people even want to be driven around by a computer. Maybe that’s just a person in a car pretending to be a computer.

Why This Is Emotionally Tough

It is hard to release something that isn’t finished. We are afraid of looking stupid or having people reject our idea. But Ries makes a great point: if you wait until it is perfect, you are just delaying the moment you find out you were wrong. It is much better to find out your idea is bad on day ten than on day three hundred.

How to Start Using This Today

To apply Chapter 5, stop planning and start interacting.

- List your top three leap-of-faith assumptions.

- Go talk to five potential customers today. Don’t pitch them. Just listen to their problems.

- Ask yourself: what is the smallest possible thing I can build to see if these people will actually give me their time or money?

This chapter is the bridge between thinking and doing. It forces you to stop hiding behind your computer and start engaging with reality.

Chapter 6: Test

If you followed the “Leap” in the last chapter, you are now standing on a set of assumptions. Chapter 6 is about the reality check.

Eric Ries calls this chapter Test because it is time to stop talking and start building the Minimum Viable Product (MVP).

The MVP Is a Learning Tool, Not a Product

This is the most misunderstood concept in the entire book. Most people think an MVP is just a “lite” version of their product or a crappy version with half the features.

That is wrong. An MVP is the fastest way to get through the Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop with the minimum amount of effort. Its goal is not to be a good product; its goal is to test your business hypotheses.

Types of MVPs That Actually Work

Ries shares some brilliant examples of how to test an idea without actually building the technology first.

- The Video MVP (Dropbox): Before they wrote a single line of complex code, the founder of Dropbox made a simple three-minute video showing how the product would work. It was a fake demo. But it drove their waiting list from 5,000 to 75,000 people overnight. They hadn’t built the software, but they had validated the demand.

- The Concierge MVP (Food on the Table): Instead of building an automated app for meal planning, the founders went to the grocery store with individual customers and manually picked out their food. They did the work by hand to learn exactly what the customer cared about before they ever automated it.

- The Wizard of Oz MVP (Aardvark): This is where you make it look like a computer is doing the work on the front end, but a human is actually pulling the levers behind a curtain. You simulate the technology to see if people even want the result.

The Quality Challenge

Here is a moment to challenge your ego. As a professional, you probably take pride in your work. You want it to be high quality.

But here is the danger: Startups often do not know what quality means to their customers yet. If you spend months polishing a feature that nobody wants, you aren’t being high quality ; you are being wasteful.

In the early stages, quality is defined by how well you solve the customer’s problem, not how clean your code is or how pretty your logo looks.

Speed Is Your Only Real Advantage

Startups are in a race against time. Your runway isn’t just about money; it is about how many pivots you have left. By using an MVP, you are buying yourself more chances to get it right.

If you spend all your money on one big perfect launch, you only get one shot. If you use MVPs, you might get ten shots at the same cost.

How to Use This Today

If you are ready to test your idea, don’t open a code editor or hire a designer.

- Ask: what is the cheapest possible way to see if a customer will actually take the action I want them to take?

- Don’t be afraid to do things that don’t scale. Manual work is okay if it leads to learning.

- Measure behaviour, not opinions. Don’t ask if they like it; see if they sign up, click, or pay.

This chapter is a call to be brave enough to be imperfect. It is about realizing that your initial vision is probably wrong in some ways, and the sooner you find those flaws, the sooner you can build something that actually changes the world.

Chapter 7: Measure

Chapter 7 is all about Innovation Accounting. Eric Ries knows that the boring part of a startup is the accounting, but he argues that if you don’t measure the right things, you are just playing at business rather than building one.

The Baseline: Where Are You Now?

To know if you are making progress, you first have to know where you are starting. Ries suggests using your Minimum Viable Product (MVP) to establish a baseline.

Imagine you launch a new fitness app. Your baseline might show that only 5% of people who download the app actually finish their first workout. This is your starting point. It isn’t a failure; it is the truth. Without this baseline, you have no way to know if any of the “improvements” you make later actually work.

The Three A’s of Metrics

Ries introduces three criteria that every metric you track must meet to be useful:

- Actionable: It must show clear cause and effect. If the number goes up or down, you should know exactly which of your actions caused that change.

- Accessible: The data needs to be simple enough that everyone in the company can understand it. You shouldn’t need a PhD in statistics to know if the week was a success.

- Auditable: You must be able to verify that the data is real. If a manager questions the numbers, you should be able to show them the actual customers behind the data.

Vanity Metrics vs. Actionable Metrics

This is where Ries gets really opinionated. He hates vanity metrics, numbers like total registered users or raw pageviews. These numbers almost always go up and to the right, which makes you feel good, but they don’t tell you anything about the health of your business.

A classic example of a vanity metric is the total number of downloads. You could have a million downloads, but if no one is actually using the app after day one, your business is a ghost town. An actionable metric would be the percentage of users who come back a second time. That number tells you if your product is actually solving a problem.

Cohort Analysis: The Truth-Teller

To get to the truth, Ries advocates for cohort analysis. Instead of looking at cumulative totals, you look at groups of customers (cohorts) based on when they joined.

For example, you might look at all the people who signed up in January and see how many are still active in March.

Then you look at the February cohort. If the February group is more active than the January group, you have validated learning that your product is getting better. If the numbers stay the same despite all your hard work, you are just tuning the engine without actually moving the car.

A Challenge to Your Success

Let’s pause for a second. It is incredibly tempting to show a graph of your total users to your boss or your investors to prove you are doing a good job.

But you are lying to yourself. If your growth is coming from spending money on ads rather than from a product that people love, you haven’t built a business; you have built an expensive hobby.

Chapter 7 forces you to be honest. It is better to have a tiny number that is growing because people actually value it than a huge number that is propped up by marketing spend.

How to Apply This Today

To use Chapter 7, you need to clean up your dashboard.

- Delete any metric that is just a total (total users, total revenue, total hits).

- Identify your North Star metric, the one number that proves your customers are getting value.

- Start grouping your users into cohorts. Compare the behavior of new users to old users to see if your latest features are actually making a difference.

This chapter turns you from a dreamer into a realist. It gives you the tools to know, with mathematical certainty, whether your startup is on the path to success or headed for a cliff.

Chapter 8: Pivot (or Persevere)

This chapter is the emotional climax of the book. Eric Ries calls it Pivot (or Persevere) because it deals with the hardest decision any entrepreneur will ever face: when to keep going and when to admit that your current strategy is failing.

What Is a Pivot, Exactly?

A pivot is a structured course correction designed to test a new fundamental hypothesis about the product, strategy, and engine of growth.

It is not just a random change or a reaction to a bad day. It is a strategic shift while staying grounded in your original vision.

Think of it like a GPS. Your destination (the vision) hasn’t changed, but the GPS has realized there is a massive traffic jam ahead, so it is rerouting you. You are still trying to get to the same place; you are just taking a different road to get there.

The Catalog of Pivots

Ries lists several ways you can pivot. Here are a few of the most practical ones:

- Zoom-in Pivot: You realize that one tiny feature of your product is actually what everyone loves. You cut everything else away and make that single feature the whole product.

- Zoom-out Pivot: The opposite happens. You realize your product is good, but it is not enough to stand on its own. It needs to become just one feature of a much larger product.

- Customer Segment Pivot: You built the right product, but for the wrong people. You shift your focus to a different group of customers who actually value what you made.

- Value Capture Pivot: You change your revenue model. Maybe you were trying to sell a subscription but realize you should be giving it away for free and charging for ads instead.

The Pivot or Persevere Meeting

This is a piece of advice you can use immediately. Ries suggests scheduling a regular meeting, perhaps every few weeks or once a month, specifically to ask this question.

In this meeting, you look at your actionable metrics (the ones we talked about in Chapter 7).

- If the numbers are moving in the right direction, you persevere.

- If the numbers have plateaued, no matter how many improvements you make, it is time to pivot.

A Challenge to Your Ego

Here is the hard part: Most people don’t pivot because they are afraid to admit they were wrong. They worry about what their investors, employees, or even their spouse will think.

But here is the mistake: Staying on a sinking ship because you are persistent isn’t brave; it is wasteful.

True perseverance is having the courage to abandon a failing strategy so you can save the vision. Failure is only a total loss if you refuse to learn from it and change direction.

Why This Is Especially Practical

This chapter reframes runway. Most people think runway is how much money you have left in the bank. Ries says your true runway is how many pivots you have left.

If you spend all your money on one big, slow launch, you have a runway of one. If you use the Lean Startup method to move fast and run cheap experiments, you might have a runway of five or ten. The more chances you have to pivot, the more likely you are to find the path that actually works.

How to Apply This Today

To use Chapter 8, you have to be brutally honest with yourself.

- Look at your “improvements” over the last three months. Have they actually moved your core metrics, or are you just “polishing a turd”?

- Schedule a Pivot or Persevere meeting for this Friday. Invite a mentor or a peer who isn’t afraid to tell you the truth.

- Ask yourself: if I were starting this company today, with the data I have now, would I build exactly what I am building?

If the answer is no, then you are already in the middle of a pivot; you just haven’t admitted it yet.

Chapter 9: Batch

Here, Eric Ries explores the surprising power of working in small batches.

He argues that even though it feels more efficient to work in large chunks, the opposite is actually true for startups.

The Envelope Paradox

Ries starts with a simple thought experiment: stuffing 100 envelopes with newsletters.

- The Large Batch Method: You fold all 100 papers first, then seal all 100 envelopes, then stamp all 100.

- The Small Batch Method: You fold, seal, and stamp one envelope at a time.

Most people believe the large batch is faster. However, in practice, the small batch method is often quicker because you don’t have to manage a huge pile of unfinished work. More importantly, if you realize the newsletter doesn’t fit in the envelope, you find out on the first one, not after you’ve already folded all 100.

The Toyota Connection: Lean Manufacturing

The concept comes from the Toyota Production System . Toyota realized that by reducing the time it took to switch machines (reducing setup time), they could produce cars in much smaller batches than their competitors.

This allowed them to:

- Respond to customer demand faster.

- Hold less inventory (which is essentially wasted money).

- Identify quality issues immediately rather than at the end of a long assembly line.

Continuous Deployment: Batches in Software

For a modern startup, this translates to Continuous Deployment. Instead of having a big launch every six months, successful tech companies often push code to their live site dozens of times per day.

If a developer makes a mistake, they find out within minutes because the batch of code they just released was tiny. If they waited six months to release a huge batch of code, finding the one bug in that massive pile would be a nightmare.

The Large Batch Death Spiral

Ries warns against the Large Batch Death Spiral. This happens when a team decides a project is too important to fail, so they add more features, which makes the batch larger, which makes it take longer, which makes the stakes even higher.

Eventually, the project becomes so big and complex that it collapses under its own weight. Small batches are the antidote to this trap.

A Challenge to Your Efficiency

Think about your work day. We are often taught to batch our emails or tasks to stay focused.

But be careful: In a startup, the unit of work is learning. If you spend a whole month batching the design of a product before showing it to anyone, you are delaying your learning. You might be efficient at designing, but you are being inefficient at building a business.

How to Apply This Today

To use Chapter 9, you need to shrink your cycle times.

- Find a task you usually do in a big chunk and try doing it in the smallest possible increment.

- Instead of planning a month-long marketing campaign, try running one ad today to see if anyone clicks.

- Ask: “How can we reduce the time it takes to get from an idea to a result that a customer can see?”

By working in small batches, you ensure that you never travel too far down the wrong path before the real world has a chance to correct you.

Chapter 10: Grow

Chapter 10 is titled Grow because it tackles the mystery of how a small idea becomes a massive, self-sustaining business.

Eric Ries argues that growth is not just a matter of luck or a big marketing budget; it is the result of a specific engine that you have to build and tune.

The Definition of Sustainable Growth

Ries defines sustainable growth with a simple rule: new customers come from the actions of past customers.

If you have to pay for every single new customer out of your own pocket or through investment money, that is not sustainable. You are just buying growth. True sustainable growth happens in four ways:

- Word of mouth: Satisfied customers tell their friends because they love the product.

- Side effect of product usage: When you see someone wearing a specific brand of headphones or using a specific app, that act of using it advertises the product to you.

- Funded advertising: You use the profit from one customer to buy an ad to find the next customer.

- Repeat purchase: Customers come back to buy again and again (like a subscription or buying groceries).

The Three Engines of Growth

Ries explains that every startup should focus on one of three primary engines to drive this sustainable growth.

1. The Sticky Engine of Growth

This engine is all about retention. If you are running a business that depends on long-term customers (like a gym or a SaaS app), your biggest enemy is churn, the rate at which customers stop using your service. To grow, your rate of new customer acquisition must be higher than your churn rate.

If you lose 10% of your customers every month, you have to find 11% new ones just to grow by 1%. If you can’t fix your churn, no amount of marketing will save you.

2. The Viral Engine of Growth

In this engine, growth happens as a mathematical side effect of using the product. Think of Hotmail or PayPal. Every time you used the product, you were exposing someone else to it. The key metric here is the viral coefficient: how many new customers will use the product as a consequence of each new customer who signs up? If one person brings in 1.1 more people, the business will grow exponentially without you spending a dime on ads.

3. The Paid Engine of Growth

This is the traditional method: you pay for ads to get customers. The secret here is the balance between Customer Lifetime Value (LTV) and Cost Per Acquisition (CPA). If it costs you $10 to get a customer, but that customer only brings in $5 of profit over their lifetime, you are losing money. To grow, your LTV must be significantly higher than your CPA. You then reinvest that margin into more ads to keep the engine turning.

A Challenge to Your Ambition

Stop and think about this for a second. Most founders try to use all three engines at once. They want a viral app that people stick with forever while also running Facebook ads.

This is a major mistake. Successful startups usually focus on one engine at a time. Each engine requires a different set of skills, different metrics, and a different mindset. Trying to do all three usually leads to doing none of them well. Focus on the one that fits your product best until you have mastered it.

The Inevitable Plateau

Every engine eventually runs out of gas. You will eventually run out of people to show ads to, or your viral loop will hit a ceiling. This is the moment most companies panic and start doing random things.

The Lean Startup approach tells you to prepare for this by innovation accounting. When you see your engine starting to plateau, that is the signal that it is time to pivot or find your next engine of growth.

How to Apply This Today

To use Chapter 10, you need to identify your engine.

- Which of the three engines is most natural for your product?

- Find your North Star metric for that engine (Churn for Sticky, Viral Coefficient for Viral, or Margin for Paid).

- Ignore everything else for a month and focus 100% of your experiments on moving that one number.

Growth is not a mystery; it is a machine. Once you understand which machine you are building, you can stop guessing and start engineering your success.

Chapter 11: Adapt

Eric Ries addresses a common fear here that asks. as startup grows, will it become a slow, bureaucratic nightmare? He argues that you don’t have to choose between speed and stability. Instead, you need to build an adaptive organization that automatically adjusts its processes based on the problems it encounters.

The Wisdom of the Five Whys

The heart of this chapter is a technique called the Five Whys. It is a simple but brutal tool for getting to the root of any problem.

The idea is that behind every technical problem is usually a human problem. If a server crashes, don’t just fix the server. Ask why it happened.

- Why did the server crash? (Because a new piece of code broke it).

- Why did the code break it? (Because it wasn’t tested properly).

- Why wasn’t it tested properly? (Because the developer didn’t know how to use the test tool).

- Why didn’t they know how to use it? (Because their manager didn’t train them).

- Why didn’t the manager train them? (Because they were too busy hitting a deadline).

Suddenly, a technical glitch is revealed to be a training and management issue. If you only fix the server, it will crash again. If you fix the training process, you solve the problem forever.

The Proportional Investment Rule

This is the most practical way to use the Five Whys without going crazy. Ries suggests that you should make a proportional investment in prevention at each of the five levels.

If a problem is small, spend a little time on it. If it is a disaster, spend a lot. This prevents you from over-engineering solutions for tiny glitches while ensuring that major systemic failures actually get fixed. It allows the company to develop just enough process to stay safe without slowing down to a crawl.

A Challenge to Your Blame Game

Stop and look at how you react to mistakes. When something goes wrong, is your first instinct to find out who messed up?

This is a major error. Most mistakes are the result of a bad system, not a bad person. If you blame people, they will start hiding their mistakes to protect themselves. When people hide mistakes, the Five Whys becomes impossible to use. To be an adaptive organization, you have to create a culture where it is safe to admit when something is broken so the system can learn from it.

Starting Small with Adaptive Processes

You don’t need to change your whole company overnight. Ries suggests starting with a single team. When they run into a snag, have them sit down and do a Five Whys session.

- Keep the meetings short.

- Be tolerant of first-time mistakes but never allow the same mistake to happen twice.

- Ensure that the people affected by the problem are the ones in the room.

Why This Is Hard to Apply

The Five Whys can feel like a “blame session” if you aren’t careful. It requires a high level of trust. It also takes time away from building new features, which can feel like you are slowing down. But as Ries points out, those “speedy” teams that don’t fix their systems eventually get bogged down by “technical debt” until they can’t move at all. Investing in adaptation is how you stay fast in the long run.

How to Apply This Today

The next time a project misses a deadline or a mistake is made:

- Resist the urge to just “fix it and move on.”

- Gather the team for 15 minutes and ask “Why?” five times.

- Identify the human/process cause and make one small, cheap change to prevent it from happening again.

By doing this, you turn every failure into an upgrade for your organization.

Chapter 12: Innovate

In Chapter 12, Eric Ries addresses the Innovator’s Dilemma, the struggle established companies face when trying to innovate while maintaining their existing business.

He argues that innovation shouldn’t be a separate department but a core capability of the entire organization.

The Innovation Sandbox

Ries introduces the concept of an Innovation Sandbox. This is a safe environment where internal teams can run experiments without risking the company’s entire reputation or bottom line.

A sandbox has strict rules:

- Small Scale: Experiments only affect a tiny, specific segment of the customer base.

- Short Duration: Teams must be able to complete the experiment in a set amount of time.

- Standardized Metrics: Every experiment in the sandbox must be evaluated using the same set of actionable metrics.

- Transparency: Anyone in the company can see what experiments are running and what the results are.

This allows teams to move with the speed of a startup while the parent company provides the resources and stability.

Cultivating an Internal Startup Culture

To successfully innovate from within, Ries suggests three key structural changes:

- Scarce but Secure Resources: Innovation teams don’t need a massive budget; they need a guaranteed budget. Having too much money can actually lead to waste and lack of focus.

- Independent Development Authority: Teams must have the power to make decisions and ship products without needing a dozen signatures from middle management.

- Personal Stake in the Outcome: Founders of internal startups should have a tangible incentive—whether it’s equity, a bonus, or career advancement—to make the project succeed.

The Portfolio Approach

Large companies should view their projects as a Portfolio.

- Core Businesses: These are the “cash cows” that provide steady revenue.

- Adjacent Innovations: These are improvements to existing products for new markets.

- Transformational Innovations: These are the “moonshots”—completely new products for markets that don’t exist yet.

Ries argues that companies often starve their transformational projects because they don’t show immediate ROI. By applying Innovation Accounting (from Chapter 7), leadership can measure the learning these projects generate rather than just the profit.

A Challenge to Corporate Thinking

Stop and think about your workplace. When someone has a new idea, is the first reaction “Why won’t this work?” or “How can we test this?”

This is the culture gap. In a Lean Startup, the goal is to eliminate uncertainty, not to avoid risk. If your organization punishes failed experiments, you aren’t being careful; you are actively killing your future.

You must create a culture where validated learning is celebrated as much as a quarterly profit increase.

How to Apply This Today

Whether you are in a giant corporation or a ten-person shop, you can use Chapter 12:

- Identify a sandbox project, a small experiment you can run with minimal oversight.

- Define your fail-safe: what is the worst-case scenario if this experiment fails, and how can you minimize it?

- Report your results in terms of customer behavior, not just internal milestones.

By building these small islands of innovation, you ensure that your company can adapt to the future instead of being disrupted by it.

The Epilogue of The Lean Startup is Eric Ries’s call to action. He steps back from the specific how-to of building a business to look at the bigger picture: the impact of the Lean Startup movement on society and the future of work.

Epilogue: Waste Not

The core theme of the Epilogue is that waste is the enemy of human potential. Ries argues that the greatest waste in our world today is not of money or natural resources, but of human time spent building things that nobody wants.

The Responsibility of Management

Ries argues that we have a societal responsibility to stop wasting people’s lives in success theatre the practice of looking busy and hitting meaningless milestones while the actual product is failing.

He suggests that:

Management is a noble profession. When done correctly, it provides the structure that allows people to be creative and impactful.

Innovation is the new management. In an era of high uncertainty, the old methods of command and control are obsolete. We need a management style built for discovery.

The Long-Term Stock Exchange (LTSE)

One of the most practical visions Ries shares in the Epilogue is his idea for a Long-Term Stock Exchange.

He believes that modern public markets force companies to focus on short-term quarterly profits, which is the anti-Lean Startup. A company focused on the next three months cannot afford to experiment or pivot. His vision for the LTSE is a marketplace that rewards long-term thinking and validated learning over short-term financial engineering.

A Global Movement

Ries concludes by noting that the Lean Startup is no longer just for high-tech software companies in Silicon Valley. It has become a global movement used by:

- Governments trying to deliver better services to citizens with fewer resources.

- Non-profits trying to solve social problems more effectively.

- Large enterprises trying to stay relevant in a changing world.

The Final Word: Start Now

The book ends with a simple challenge: Don’t just read about validated learning; start doing it.

The mistake many people make: They wait until they have a perfect plan or a complete team. Ries reminds us that the whole point of the Lean Startup is that you cannot know the perfect plan in advance. The only way to find it is to Build-Measure-Learn your way there.

How to Apply the Epilogue Today

To honor the spirit of the conclusion, ask yourself one final question:

“What is the most important thing I need to learn right now, and what is the smallest possible experiment I can run to learn it?”

Stop planning. Stop debating. Go out and test your hypothesis.

Here are the things you need to do starting from now to implement the principles in The Lean Startup

Takeaway 1: Identify Your Leap of Faith Assumption

The easiest way to start is to admit what you are guessing about. Every new project is built on a few big guesses that, if wrong, mean the project will fail.

- Step 1: Take a piece of paper and draw a line down the middle.

- Step 2: On the left, write down what you think will happen. For example: People will pay $20 for my homemade jam.

- Step 3: On the right, write down the assumption behind that. Example: People actually like the taste of my jam enough to pay for it.

- Step 4: Circle the one assumption that is the most dangerous. This is your leap of faith.

Small Start Today Action: Spend 10 minutes in your phone notes app. List the top three reasons why your current project might fail. Be brutally honest.

When and Where: Do this tonight before bed while sitting on your couch. Use your phone notes app so you can look at it later.

Timeline and Progress: You should see results in 1 to 2 days. Progress looks like having a clear, written statement of what you need to prove first.

Challenges and Mistakes: Beginners often pick assumptions that are too broad, like “people like food.” Instead, be specific: “people like this specific flavour.”

How to Overcome: Ask yourself: “If this one sentence is false, is my project dead?” If yes, that is your leap of faith. Avoid This: Do not spend hours making a beautiful logo or website. It feels productive, but it does nothing to test your assumption.

Metric to Track: Completion of a written list of 3 specific assumptions.

Reflection Question: If you found out today that your main assumption was false, would you be relieved to know now or would you keep trying anyway?

Takeaway 2: Conduct a Genchi Gembutsu (Go and See)

You cannot learn about your customers from your desk. You have to observe them in their natural habitat.

- Step 1: Identify where your potential customers hang out. This could be a specific coffee shop, a Facebook group, or a physical store.

- Step 2: Go to that place and just watch. Do not talk yet. Watch how they interact with products similar to yours.

- Step 3: Write down three problems you see them having.

Small Start Today Action: Spend 15 minutes browsing a Reddit thread or an Amazon review section for a product similar to your idea. Look for the one-star reviews. What are people complaining about?

When and Where: Do this during your lunch break tomorrow. Use a physical notebook to jot down observations.

Timeline and Progress: 1 week. Progress looks like a list of real-world pain points that you didn’t just make up in your head.

Challenges and Mistakes: Beginners often try to lead the witness by asking “Would you buy this?” People will say yes just to be nice. How to Overcome: Don’t pitch. Just ask about their past behaviour. “When was the last time you bought X?” Avoid This: Avoid sending out a mass survey. Surveys are easy but people lie on them. One-on-one observation is much harder but much more accurate.

Metric to Track: Number of pain points identified from actual observation (target: 5).

Reflection Question: Did the people you observed actually have the problem you thought they had, or did you see a different problem?

Takeaway 3: Build a Smoke Test (Your first MVP)

You don’t need a product to see if people want it. A smoke test is a way to see if people will click before you build the engine.

- Step 1: Create a simple one-page description of your service. You can use a free tool like Google Docs or a simple social media post.

- Step 2: Include a clear call to action, such as Enter your email for early access or Send me a DM to pre-order.

- Step 3: Share that link with ten people who don’t know you personally.

Small Start Today Action: Draft a 3-sentence post explaining your idea as if it already exists. Put it in your drafts but don’t post it yet.

When and Where: Saturday morning at 10:00 AM. Use your laptop or a tablet.

Timeline and Progress: 1 to 2 weeks. Progress is seeing a conversion rate. If 10 people see it and 0 sign up, you have a problem.

Challenges and Mistakes: Trying to make the page look perfect. How to Overcome: Remind yourself that this is an experiment, not a launch. If it fails, you can delete it and no one will care. Avoid This: Do not buy a custom domain name or pay for hosting yet. Use free versions of everything.

Metric to Track: Conversion rate (Number of sign-ups divided by number of people who saw the page).

Reflection Question: If no one signs up for your smoke test, are you willing to change your idea, or are you too attached to it?

Takeaway 4: Establish a Baseline with Actionable Metrics

You need to know what normal looks like so you can tell if your changes actually help.

- Step 1: Pick one number that matters. If you are selling something, it is the number of sales. If you are writing, it is the number of people who read to the end.

- Step 2: Track that number for one week without changing anything. This is your baseline.

- Step 3: Put this number on a calendar where you can see it every day.

Small Start Today Action: Look at whatever you are currently doing and find one number you can track. Write down what that number was for yesterday.

When and Where: Do this at your desk at the start of your workday tomorrow. Use a physical wall calendar or a simple spreadsheet.

Timeline and Progress: 2 to 4 weeks. Progress looks like a steady line of data that tells you exactly how your project is performing.

Challenges and Mistakes: Tracking vanity metrics like total followers or hits. These go up even if your business is dying. How to Overcome: Only track numbers that lead to a specific decision. Avoid This: Avoid checking your stats every hour. It feels like work but it is just a distraction. Check once a day at most.

Metric to Track: Consistency of daily tracking (target: 7 days in a row).

Reflection Question: Does this number actually prove people value what you are doing, or does it just make you feel good?

Takeaway 5: Run a Five Whys Session

When something goes wrong, don’t just fix the surface. Find the human cause.

- Step 1: Pick a recent mistake or failure in your project.

- Step 2: Ask why it happened. Write down the answer.

- Step 3: Ask why that answer happened. Do this five times until you hit a process or a behaviour you can change.

- Step 4: Fix the process, not the person.

Small Start Today Action: Think of one thing that frustrated you today. Ask yourself “Why?” five times to see if it was actually your fault or a bad system you have.

When and Where: Friday afternoon at 4:00 PM. Use a notebook or a whiteboard.

Timeline and Progress: Months. Progress looks like fewer repeat mistakes. You should feel like you are solving problems once instead of over and over.

Challenges and Mistakes: Using the Five Whys to blame people. How to Overcome: If the answer is “someone was lazy,” you haven’t gone deep enough. Ask “Why did the system allow them to be lazy?” Avoid This: Do not skip the fourth or fifth “Why.” The first three are usually just symptoms.

Metric to Track: Number of recurring problems that have been permanently solved.

Reflection Question: Are you willing to admit that a failure was caused by a flaw in your own system?

Takeaway 6: Schedule a Pivot or Persevere Meeting

This is the hardest part. You must force yourself to decide if your current path is working.

- Step 1: Set a recurring meeting on your calendar for every 4 weeks. Label it “Pivot or Persevere.”

- Step 2: Bring your actionable metrics and your leap of faith assumptions to the meeting.

- Step 3: Compare your actual results to your baseline. If the numbers aren’t moving despite your efforts, you must change your strategy (Pivot).

Small Start Today Action: Open your digital calendar and create a 30-minute appointment for four weeks from today. Invite one person you trust to hold you accountable.

When and Where: Set the calendar invite now on your phone.

Timeline and Progress: 3 to 6 months. Progress looks like having the courage to abandon a bad strategy before you run out of money or energy.

Challenges and Mistakes: Emotional attachment. We don’t want to admit our baby is ugly. How to Overcome: Focus on the vision, not the path. If your vision is to help people eat better, the specific jam you are selling is just one path. If it fails, pick another path. Avoid This: Avoid delaying the meeting because you want one more week of data. The data you have is usually enough to know the truth.

Metric to Track: Attendance and completion of the monthly meeting.

Reflection Question: If you had to start your project from scratch today, knowing what you know now, would you build exactly what you have?

Eric Ries is an American entrepreneur, author, and pioneer of the Lean Startup movement.

Born in 1978, Ries studied computer science at Yale University, where he became involved in several startup projects.

His early ventures included a role as a software engineer at There.com, a 3D social network that ultimately failed, which provided him with valuable lessons on startup failure.

In 2004, Ries co-founded IMVU, a social entertainment company that allowed users to create 3D avatars and interact in virtual spaces.

It was during his time at IMVU that Ries began developing the ideas that would later become the Lean Startup methodology.

The challenges he faced in product development and market testing at IMVU led him to rethink traditional approaches to entrepreneurship.

“The Lean Startup” was published in 2011 and quickly became a bestseller, widely regarded as one of the most influential business books of the decade.

The book formalized the principles of the Lean Startup, which include the concepts of validated learning, the Minimum Viable Product (MVP), and the Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop.

Ries has since become a sought-after speaker, advisor, and thought leader in the startup community.

He has worked with large companies and organizations, helping them apply Lean Startup principles to foster innovation and agility.

In addition to “The Lean Startup,” Ries is also the author of “The Startup Way” (2017), which explores how larger organizations can innovate and grow using Lean Startup principles.

- Title: The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses

- Author: Eric Ries

- Publication Date: September 13, 2011

- Publisher: Crown Business

- Pages: 336

- ISBN: 978-0307887894

- Genre: Business, Entrepreneurship, Management

- Available in e-book, hard cover and audiobook versions

Test your Knowledge of The Lean Startup

-

Start your The Lean Startup Quiz